What I See in My Dreams Using Art to Heal Invisible Wounds

In September 2005, I was deployed to Nigeria equally a clinical psychologist by Medicines Sans Frontiers/Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The emergency response followed a series of outbreaks of violence in the central Nigerian country of Plateau. In early May 2004 thousands of Nigerians fled from central Plateau Land after clashes between rival militia culminated in a serial of massacres. In the firsthand aftermath of this horrendous tragedy, MSF created mobile clinics to medically aid more than x,000 displaced people living in makeshift camps nether extremely difficult atmospheric condition.

In September 2005, I was deployed to Nigeria equally a clinical psychologist by Medicines Sans Frontiers/Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The emergency response followed a series of outbreaks of violence in the central Nigerian country of Plateau. In early May 2004 thousands of Nigerians fled from central Plateau Land after clashes between rival militia culminated in a serial of massacres. In the firsthand aftermath of this horrendous tragedy, MSF created mobile clinics to medically aid more than x,000 displaced people living in makeshift camps nether extremely difficult atmospheric condition.

Two especially savage attacks took place in Yelwa, a market town located in the southern part of Plateau Land. On February 4, 2004, armed Muslims killed more than 75 Christians and in an deed of retaliation, on May 2 and iii, big numbers of armed Christians surrounded Yelwa, and killed more than than 700 Muslims. Much of the urban center was destroyed and thousands of people were displaced.

MSF provided emergency medical aid to those who had fled Yelwa and helped with reintegration efforts in one case the violence had subsided. While treating many physically injured adults and children in displaced persons camps, members of the MSF team began hearing the horrific stories of what people had experienced during the attacks. The team realized that many survivors, including children, were experiencing acute trauma responses, including numbing, emotional detachment, muteness, depersonalization, psychogenic amnesia. They also had continued re-experiencing of the event via thoughts, dreams and flashbacks, as well every bit avoidance of any stimulation that reminded them of the upshot. MSF recruited me to help launch a psychosocial program aimed at helping adults and children equally they returned habitation and tried to rebuild their shattered lives. The program we created for traumatized children used creative techniques and community support to achieve its success.

We learned much from developing and implementing this plan. Prior to this I had just used art therapy in the United States with adults and children who have either survived a traumatic upshot or were coping with a traumatic loss. What we designed became the first of many projects in which I integrated fine art therapy to assist people recover from trauma in disaster contexts globally. The events that occurred in this village in Nigeria inverse my life, and showed me the power of art therapy to help heal seemingly unbearable trauma among survivors of heinous crimes. During my tenure in Yelwa MSF provided art therapy and counseling to approximately 2,500 children enrolled in schools in Yelwa and the surrounding area. The story that follows summarizes how our piece of work helped trauma victims and became a catalyst for future integrative projects.

(Fifty) Church building in Yelwa, where at least 48 Christians were killed on February 24, 2004 (R) Cardinal mosque, Yelwa, destroyed during the May 2004 assault © Human being Rights Watch

Arriving

Among the offset things I saw when driving into Yelwa in our white Land Cruiser were crumbled buildings and mass grave sites, eerie reminders of the vicious attacks that had occured just a year prior to my arrival. After the attacks marketplace life was initially deficient in Yelwa and in the surrounding towns of Garkaka and Longvel. A pulse gradually returned to these previously lively towns and when I arrived street life was back in full swing.

The vendors weren't the only people who had dissappeared from the streets in the aftermath of the attacks. My colleagues informed me that there was a noticible absenteeism of police force and military, something that many people viewed with suspicion. Once a war machine presence returned roadblocks became commonplace on the roads into Yelwa. At kickoff, MSF gave out condoms—a coveted commodity in a land where HIV is rampant—every bit a way to speedily pass through the road blocks. Nosotros rapidly learned even so, that this practice was affecting others who were too trying to laissez passer through the roadblocks as they had naught to give (see text box folio sixteen).

Getting Started

When it comes to mental health services following human-fabricated disasters, building relationships and trust is an obligation, not an choice. Therefore, nosotros quickly adamant that the local squad of counselors selected from the customs and trained on bones mental health skills would need to represent both sides of the conflict—men and women, Christians and Muslims. After a rather large circular of interviews, which included role play, a team of five local counselors were selected. I became their clinical supervisor and trainer. The kickoff round of intensive preparation lasted one month. All of the new counselors had experienced the violence kickoff manus, meaning they were both survivors and providers, and they ofttimes needed boosted support to work through their own trauma experiences tied to the crisis. The material processed in grouping supervision mirrored the problems faced in the community. For example, bug related to trust between the Christian and Muslim counselors played out right there in our supervision meetings and the counselors were able to process and make meaning of this experience both as professionals likewise as members of their respective communities. This helped them facilitate their trauma groups and work with community members from different groups and see issues from multiple perspectives.

Together we examined stereotypes and biases and team dynamics improved as accurate relationships were formed and maintained. That determination to have a representative team was a game-changer. The diverse team of psychosocial counselors quickly became known equally the "Fab V." Equally the trust amid team members grew, so did the numbers of referrals nosotros received to our support groups and school-based fine art therapy programs. Within a few months we had a expect list for services and I was given approval to hire an additional counselor. The team was after referred to equally "Fab Five Plus One." They were respected and consulted frequently because they could diplomatically update the international staff on the nuances of the conflict in a matter of minutes and help us get the root cause of any social, cultural, or governmental roadblock put in our manner.

Project Construction

Psychoeducation

In the treatment literature, much attention is paid to the cognitive and emotional processing of traumatic memories (Briere, 2003; Allen, 1991; Flack, Litz, & Keane, 1998; Friedman, 2000a; Najavits, 2002). Even so, psycho-education is also an important aspect of the early stages of trauma recovery. Many survivors of interpersonal violence were victimized in the context of an established human relationship to their perpetrator or in this example, perpetrators. Every bit a upshot, the traumatic experience is difficult to make sense of; and, in the case of children, it occurs at a relatively early stage of cerebral development. This lack of cerebral development impairs their power to accurately and coherently understand what has happened.

Child survivors ofttimes carry fragmented, incomplete, or inaccurate explanations of traumatic events into adulthood, with anticipated negative results. Psychoeducational activities are therefore helpful in the therapy process. As the customer addresses traumatic material, he or she may gain from additional information that normalizes or provides a new perspective on their traumatic memory. Our local Nigerian psychosocial counselors assisted in this area past providing accurate information to their clients on the nature of trauma and its effects on both the survivor as well as on his or her back up organization.

Children are one of the about nether-served populations amidst disaster survivors. When information technology comes to assessing their needs in a postal service-disharmonize or mail-disaster setting, children's chapters for resilience is often overstated by the adults and other care-givers around them. This is due to a misunderstanding of why children engage in play. Statements such as "he'southward already playing again, he'southward going to be simply fine," can be dangerous and misleading. I once watched a young girl practice calling 911 over and over again while "playing" with a large doll house. During therapy, I learned she blamed herself for her mother'southward expiry because she believed she did not call for aid early enough. This had not been discovered during the initial interviews because this young daughter was dissociated and highly emotionally regulated. For all intents and purposes, she looked to be coping simply "fine." What appeared to be resilience and control was actually a masking of much deeper fears and regrets.

Disasters can have far reaching and long-lasting effects on the mental health of a child. Some children can announced "just fine" in the immediate backwash, only to suffer profoundly down the route with all sorts of problems, including sleeping problems, trust and intimacy issues, emotional regulation, frustration tolerance, and cocky-soothing deficits. Art therapy in the immediate aftermath of disaster has been demonstrated—past the team in Yelwa and many other scenarios-- to be effective in reducing these impacts on children (Roje 1995, Orr, 2007, Chilicote 2007, Howie et. al 2002).

Projection Launch

The MSF mental health team get-go visited schools and community leaders in Yelwa to explain how children might manifest their trauma. Difficulty concentrating, crying jags, condign easily upset in the classroom, missing schoolhouse, poor academic operation and/or substance use were oftentimes reported. One time educated virtually the impact of trauma and trauma responses, the teachers in Yelwa felt empowered by new information and could brand sense of what appeared to be senseless behavior. Their attitudes changed, their frustrations decreased and they rapidly became our best referral source. Taking time to educate the instructor about trauma was a way to offer them support.

Clinical Programming

In group or individual sessions, participating children learned how their feelings and behaviors were linked to their personal experiences. MSF counselors used drama, drawings, breathing techniques, and well-nigh of all, talking and listening. Regularly talking and listening to others helped participants put their ain problems in perspective. They learned that while many children were struggling to make sense of what happened, few were speaking openly about it. They also realized they were not the only ones struggling, and they were relieved to hear others discuss what they were experiencing. This exchange amongst children helped to reduce the obvious (conduct disordered) problematic behavior and the non-and then-obvious (dissociated, shut down) behavior teachers were seeing in the classroom and family members were seeing at home. Both the obvious and less obvious behaviors are important to notation considering sometimes information technology is but the children who are "acting out" that are identified for help. Children who are shut downwards should as well exist assessed and supported.

The art-based intervention that was developed for this project lasted 6 sessions and included pre- and post interviews of the participants who ranged in historic period from half dozen to xviii. Both Muslims and Christian children took part. At the end of the intervention, they evaluated the local counselors. During the class of the intervention the MSF psychosocial squad focused on the following topics: establishing rubber, remembrance and mourning, bridging life before and after the traumatic effect, and exploring the children's hopes and dreams for the future. Along with a semi-structured discussion, the MSF psychosocial counselors distributed paper and pens and created a safe space and then that the children could freely depict a picture show that aligned with the topic nether discussion.

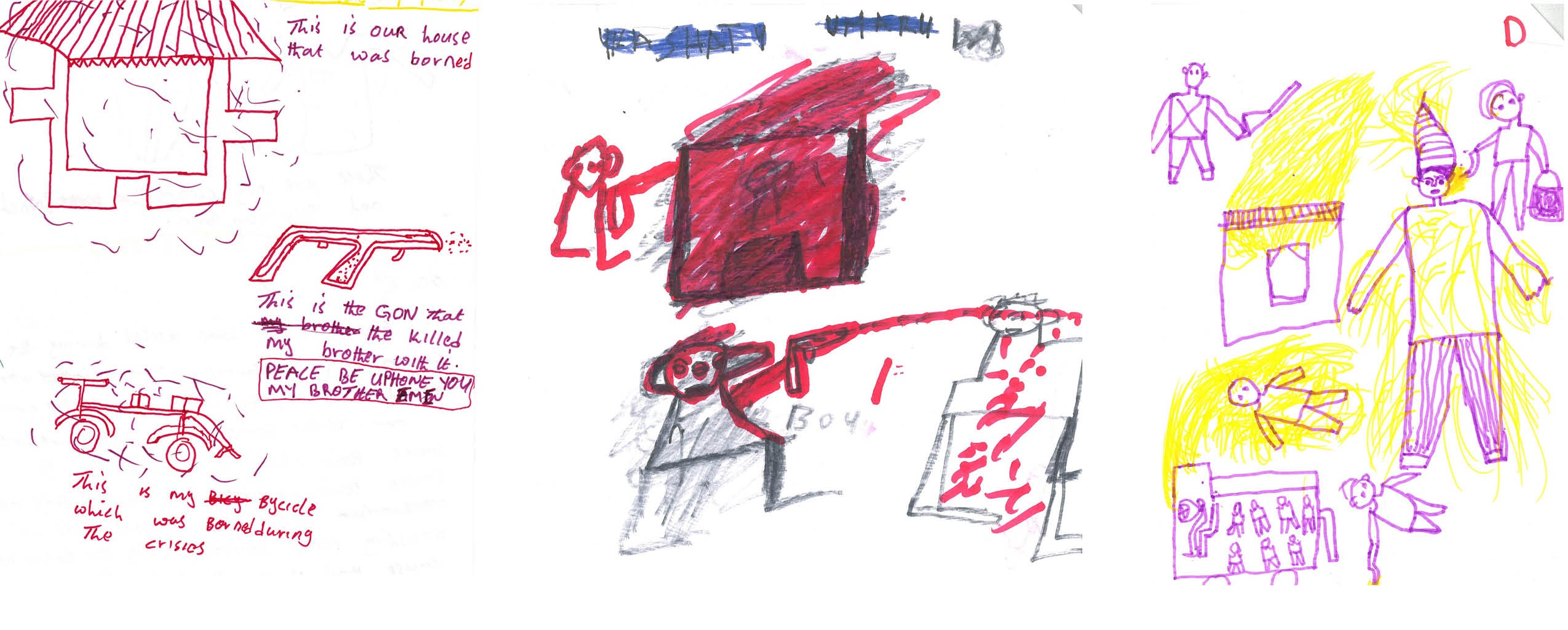

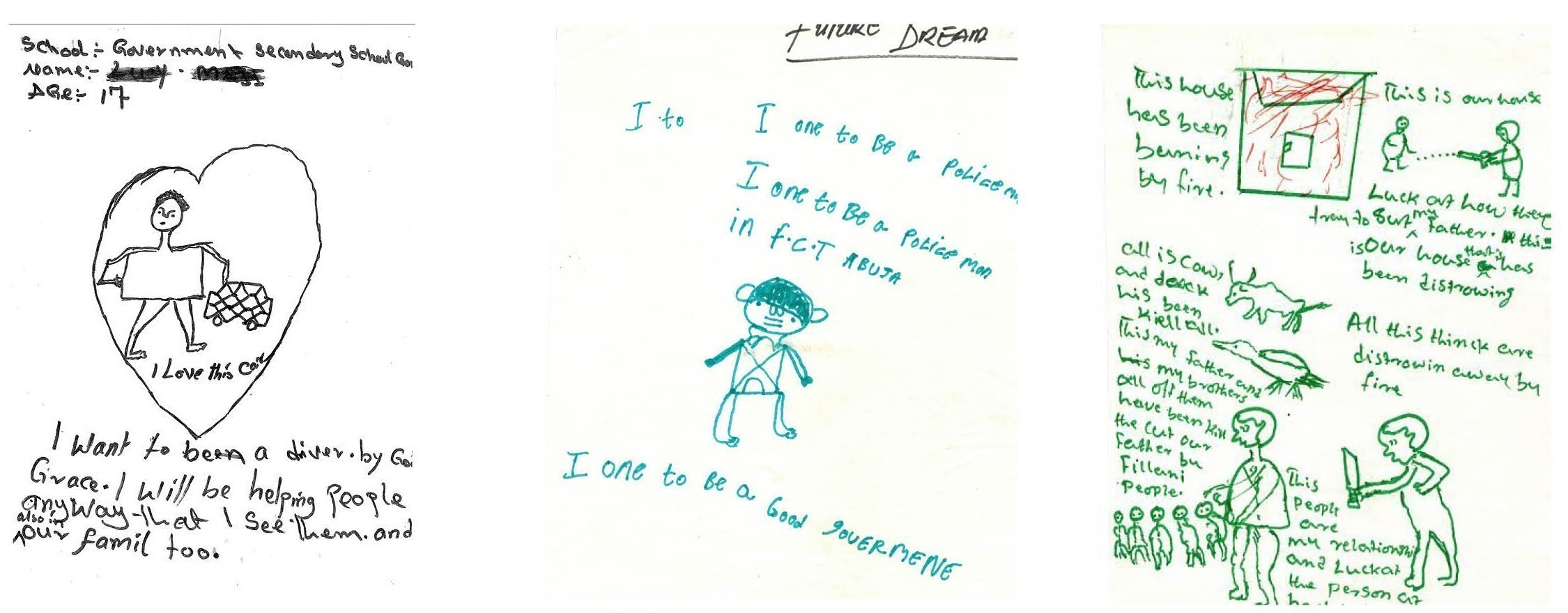

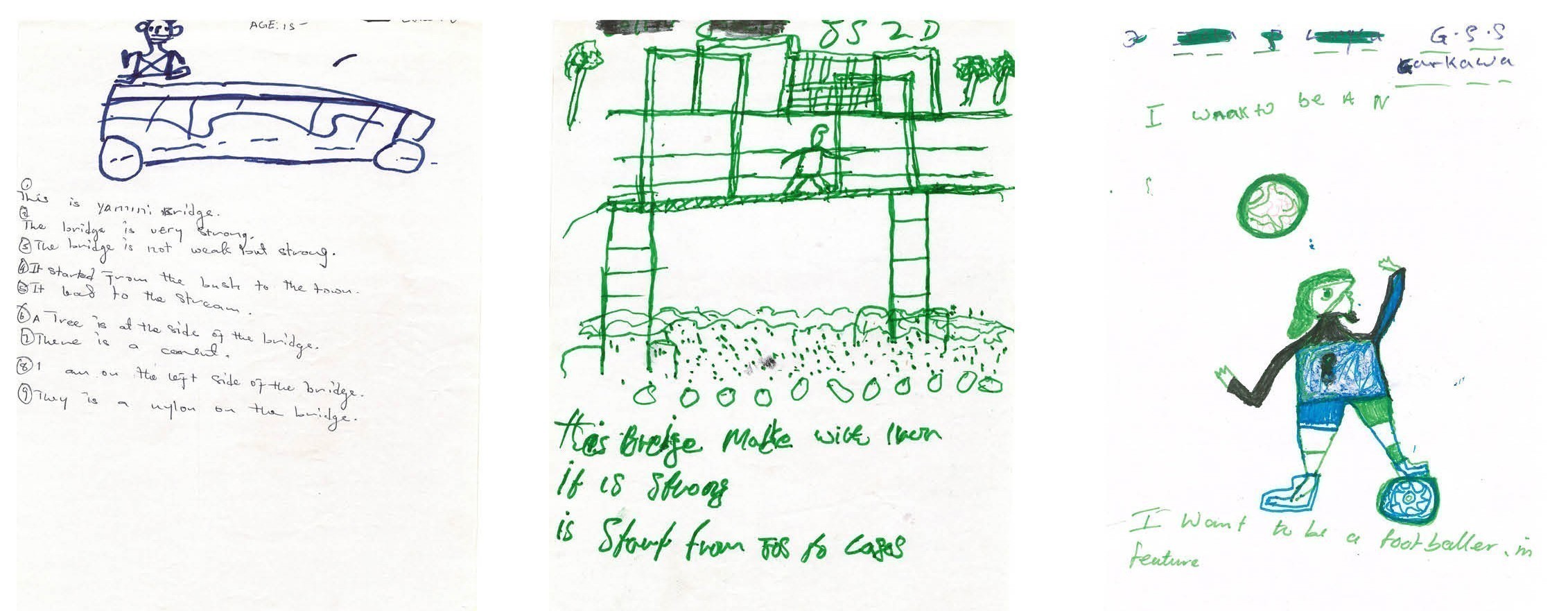

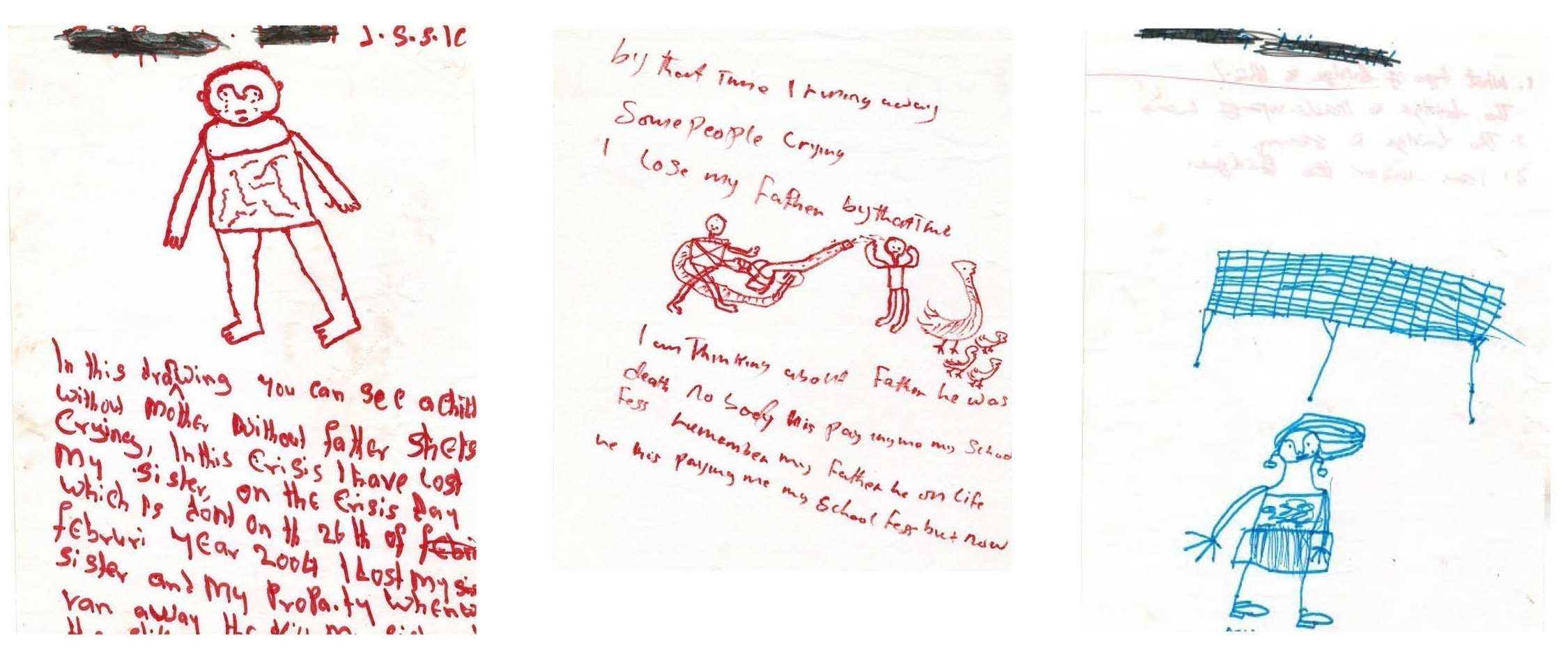

In the get-go weeks the youngsters aptitude over their pieces of paper, concentrating intensely as horrific scenes took shape: men with oversized weapons, people riddled with bullets, burning houses, and people with severed limbs. I male child even captured on paper what had happened at the local soccer field: a heinous event where 3 young men from the customs were brutally murdered on the field. This drawing sheds low-cal on the bizarre abstention and resistance many teachers and parents were seeing from their children when encouraged to "just go play futbal." Afterward, the students focused on cartoon elaborate bridges. The bridge symbolizes an individual's perception of the world (dangerous or prophylactic) and of his or her command over the surroundings (low or high). Each participant was asked to draw a bridge and place him or herself in the picture. They also drew soccer stars and medical doctors, capturing their dreams for the time to come and how they might achieve them.

During the different activities, the local counselors asked the children to explain their drawings and listened to the descriptions: father shot, uncle decapitated, sis abducted, house ransacked and burned downwardly, sharks under the shaky bridge to safety, dreams of becoming a teacher. The children recounted hundreds of traumatic scenes in uncannily absent-minded, seemingly calm voices. The transition activities were important to help the children put space and time betwixt the traumatic events and where they hoped to be. In the dream sequence many of the children laughed and acted playful.

Over the grade of my fourth dimension in Yelwa, information technology became clear that some children strained to limited their emotions and traumatic memories verbally, merely on newspaper, where anything was off-white game, they vividly, graphically, shared their experiences in drawings. The pictures they drew captured what worried, scared, and motivated them.

Mobile Art Exhibit

At the end of the vi-week intervention, the children were asked what they wanted to do with their pictures. A few of them wanted to burn or coffin the more painful renderings, equally a mode to mourn or move by what they had experienced or lost. The local counselors offered some clients a grieving ceremony, in which they buried a picture or bundled for a symbolic funeral anniversary with family for a lost loved i. They ofttimes sang local funeral songs and reminisced about the person the child had lost. Other kids asked if their fine art could be exhibited for their families and communities to see. The clinical psychologist who values privacy above all else in me baulked at the idea of publicizing what was confidential therapeutic material. But the social justice advocate in me learned that past assuasive these children to exhibit their artwork nosotros were giving them a platform to be seen and valued equally artists and members of the community. The experience of exhibiting their work helped the children experience empowered as they were treated as artists who had accomplished something, rather than as victims or clients.

The communities in Yelwa came out in droves and the land office in Abuja, 2,000 miles abroad, also held a series of incredibly well attended events to farther highlight the program and let for the pictures to be seen. Many of the children showed signs of mail service-traumatic growth, or a positive change experienced equally a result of the struggle with a major life crisis or a traumatic issue. Further, they showed up to the mobile art exhibits in their best clothes with large smiles on their faces. The talked about feeling more secure and their beliefs in school and at home underlined this perception of growth.

This fine art therapy project was successful in helping these children break free of elements of their traumatic experiences. By simply having a prophylactic place to tell and draw their stories, the children were able to integrate horrific experiences into their lives. Most of the kids improved in multiple areas of functioning--every bit evidenced by improved performance in school and better relationships with friends and family. Since the conclusion of this project I have integrated the arts—both drawing and photography—into recovery efforts effectually the globe, including in Northern Thailand with Shan Migrants, and in Liberia with torture survivors.

Thanks to modern social media, namely Facebook, I have reconnected with three of the half dozen "Fab 5 Plus One" over the last ii years. One, tragically, died from AIDS. The other two are reportedly living happy lives with their families. Unfortunately, they are no longer working as psychosocial counselors; their lives quickly converted dorsum to the ones they were leading before MSF came to town and hired and trained them. The lack of local organizational capacity edifice and hand-off to local partners is one area of disaster response and development that could use more work. Integrating ideas about sustainability can be difficult when developing a disaster response, but is essential if an organization wants to have a lasting touch. Far too many times, good projects end when the seed funding runs out and no program for sustainability has been created.

One of the women I connected with went back to didactics and has a pocket-sized pharmacy. The other went back to schoolhouse and secured a government position in the capital of the Plateau Land.

In the Plateau region things haven't inverse much, although no violent outbursts accept occurred since the 2004 attacks. Both squad members notation the tensions between Muslims and Christians in their correspondence, merely they do not feel directly affected by these tensions and are leading stable peaceful lives.

I am grateful that I am able to stay continued to these wonderful people. I deeply relish reminiscing with them. I grinning when they remind me of things I would say wrong in Housa, their local language, such as "my bag is inside the donkey" when attempting to say "my bag is inside the car." They go on to securely affect me, both professionally and personally, and I will be forever impressed by and grateful for the work they did in the backwash of this horrific man-made disaster.

Background

Since the 2014 kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls by Boko Haram, a branch of the Islamic Country of Iraq that has been active since 2009, Nigeria has been in the news a lot (Human Rights Watch 2005). Only religious-related violence predates the emergence of Boko Haram. Africa's virtually populous nation, with 150 1000000 people, has seen a steady rise in violence between the Muslim north and Christian south of the country since its independence in 1960. Nevertheless the roots of the violence go beyond organized religion.

The 2004 disharmonize in Plateau Country, for example, stems from longstanding disputes over land, political, and economic privileges betwixt indigenous groups who consider themselves original inhabitants of a particular area, called indigenes, and those whom they view as settlers. Until 2001 these disputes had never led to large-scale loss of life, but in September of that yr, tensions of a sudden exploded in Jos, the state majuscule, and effectually i,000 people were killed in simply six days. What had started as a political disharmonize turned into a religious 1 as the ethnic dissever happened to coincide with the religious divide. The tensions betwixt indigenes and settlers became a conflict between Christians and Muslims, as both sides used religion as a rallying cry to drag other groups into the conflict. After the attacks in Jos, the violence soon spread out to other parts of the Plateau State. In the years to follow poverty and regional oppression further fueled the fire.

Despite the escalation of the conflict in this surface area since September 2001, and articulate warning signs of the likelihood of further violence, the Nigerian government did not accept whatsoever effective action and allowed the conflict to screw out of command. Finally when Yelwa was attacked on May 2 and three, 2004, the calibration of the violence could no longer be ignored. On May 18, Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo declared a state of emergency in Plateau State (Homo Rights Scout 2005).

References

Allen, J. One thousand. (2005). Coping with trauma: Hope through agreement. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Briere, J. (2003). Integrating HIV/AIDS prevention activities into psychotherapy for child sexual corruption survivors. In L. Koenig, A. O'Leary, L. Doll, & W. Pequenat (Eds), From kid sexual abuse to adult sexual adventure: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention (pp. 219–232). Washington, DC: American Psychological Clan. Chilcote, R. 50. (2007). "Fine art Therapy with Kid Seismic sea wave Survivors in Sri Lanka". Art Therapy: Journal Of The American Art Therapy Clan, 24(4), 156-162. Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books. Howie, P., Burch, B., Conrad, S., & Shambaugh, S. (2002). "Releasing trapped images: Children grapple with the reality of the September eleven attacks". Fine art Therapy, 19(iii), 100-105. Human Rights Watch. (2005, May). "Revenge in the Proper noun of Religion: The Cycle of Violence in Plateau and Kano States". Vol. 17, No. 8 (A). http://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/nigeria0505/nigeria0505.pdf, (accessed on June 15, 2015). Najavits, L. One thousand. (2002). Seeking condom: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York: Guilford. Orr, P. P. (2007). "Art therapy with children afterward a disaster: A content analysis". The Arts In Psychotherapy, 34(4), 350-361. Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1993). Cerebral processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment transmission. Newbury Park: Sage. Roje, J. (1995). "LA 94 convulsion in the optics of children: Art therapy with simple schoolhouse children who were victims of disaster". Art Therapy, 12(four), 237-243.

lilienthallogetch39.blogspot.com

Source: https://hazards.colorado.edu/article/wat-i-see-in-my-dreams-using-art-to-heal-invisible-wounds

0 Response to "What I See in My Dreams Using Art to Heal Invisible Wounds"

Post a Comment